The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the socio-demographic distribution, awareness levels and knowledge gaps related to strabismus (squint) among residents of Himachal Pradesh. The results highlight both encouraging trends in public understanding and concerning gaps that require targeted interventions to improve awareness, early diagnosis and effective management of strabismus.

The balanced gender distribution (49.8% males and 50.3% females) indicates an inclusive sampling approach, ensuring insights that reflect the awareness levels of both genders. The dominance of respondents in the economically active age groups (26-35 years: 35.3%; 36-45 years: 27%) reflects the relevance of addressing strabismus awareness among individuals who are parents, caregivers, or educators-groups that are critical for promoting early intervention in children.

Educational attainment among participants showed notable diversity, with a substantial proportion holding secondary (33.5%) and undergraduate (33.3%) qualifications. However, the presence of a significant segment with only primary education (16.8%) and no formal education (4.8%) underscores the need for simplified awareness campaigns accessible to individuals with limited literacy. Given that strabismus awareness heavily relies on understanding symptoms and treatment options, tailored educational strategies that accommodate varied educational backgrounds are essential.

Occupational data showed that homemakers (26.8%) and office workers (22.8%) represented key groups, reinforcing the importance of incorporating awareness initiatives in domestic and workplace settings. The sizable rural population (57.3%) further emphasizes the need to extend vision care campaigns to underserved areas, where access to healthcare facilities and specialized eye care may be limited. The prevalence of reduced awareness scores among rural participants underscores the need for targeted outreach programs to bridge these disparities.

The awareness assessment revealed both promising understanding and critical gaps. Encouragingly, 81% of participants correctly identified strabismus as "squint" or "crossed eyes," reflecting reasonable familiarity with the condition's basic identity. However, the fact that nearly 20% failed to recognize this indicates lingering gaps in fundamental awareness that may delay early detection and treatment.

Similarly, while 71.5% correctly linked strabismus to eye muscle imbalance-a positive indicator of knowledge regarding the physiological cause-fewer respondents (67.3%) recognized that strabismus specifically affects eye muscles, highlighting an incomplete understanding of its anatomical basis. This suggests the need for improved public education on the underlying mechanisms of strabismus to support better recognition and timely intervention.

Encouragingly, a strong majority (87.8%) understood that strabismus can impair depth perception, indicating positive awareness of its functional impact. Additionally, 86.5% correctly identified ophthalmologists as the appropriate healthcare providers for strabismus treatment, reinforcing a positive trend in healthcare-seeking behavior. However, this awareness may not consistently translate into action unless knowledge about early symptoms, risks and treatment options is reinforced.

Several gaps were identified in key areas that affect preventive behaviors. Only 60.3% recognized vitamin A as a vital nutrient supporting eye health, suggesting that awareness about dietary interventions for maintaining ocular muscle function is limited. Additionally, awareness of amblyopia (lazy eye) as a potential consequence of untreated strabismus was relatively low (63.3%), reflecting a gap in understanding the long-term visual risks associated with the condition. This finding is particularly concerning as amblyopia is a common and preventable outcome if intervention occurs early. The limited recognition of these risk factors emphasizes the need to educate the public about the consequences of ignoring strabismus symptoms.

Preventive strategies and treatment options also revealed gaps. While 72.8% correctly acknowledged eye exercises or surgery as treatment methods, a notable proportion remained unaware of modern therapeutic advancements, such as vision therapy, prism lenses and improved surgical interventions. Similarly, while 80.3% identified eye exercises as a helpful management strategy, public understanding of how such interventions improve visual alignment remains limited. Additionally, only 65.3% identified misaligned eyes as a common symptom, indicating a need for improved education on the visual signs of strabismus to facilitate earlier detection.

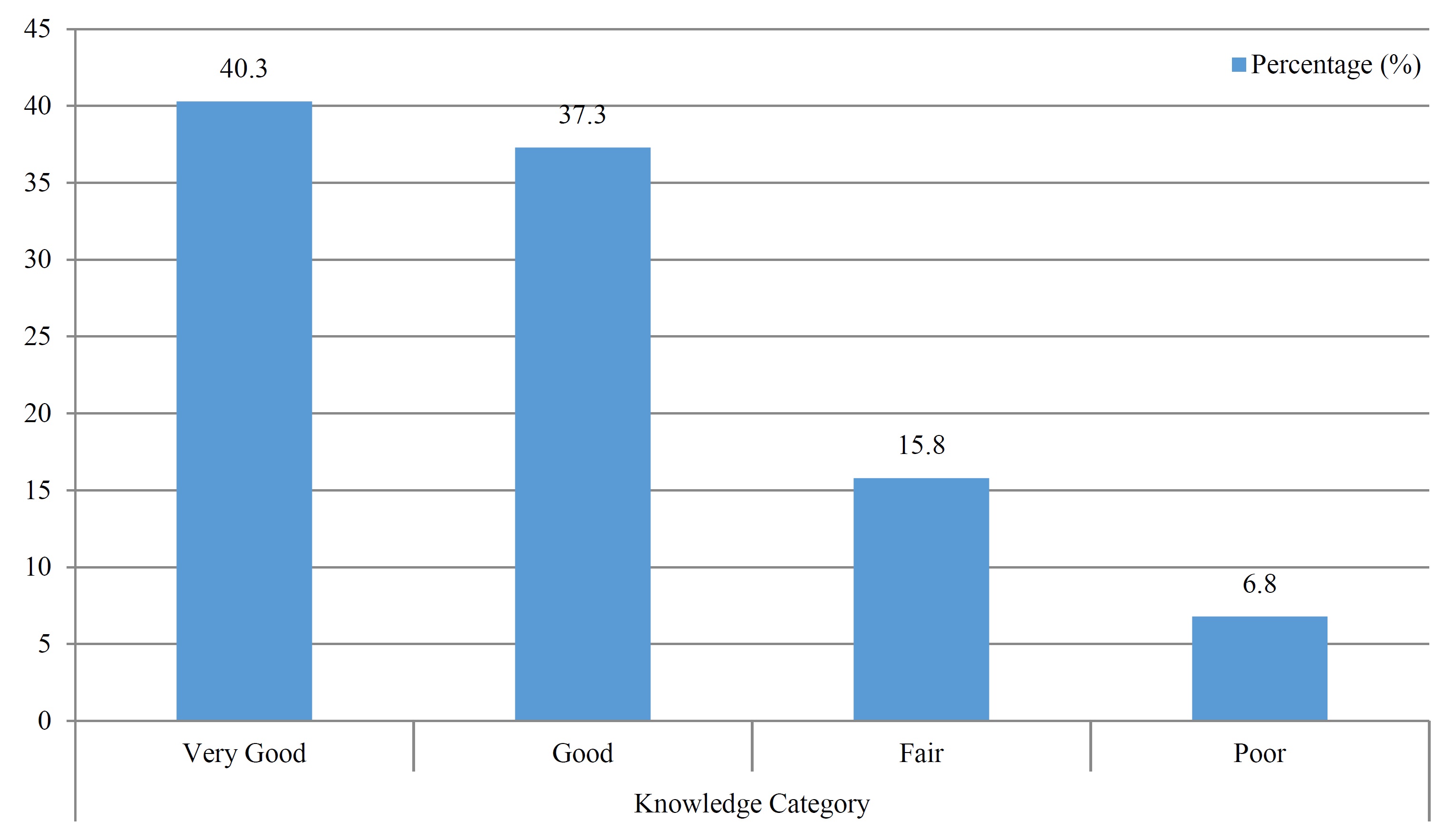

The knowledge classification further emphasized these gaps. While 40.3% of participants achieved "Very Good" knowledge scores and 37.3% achieved "Good" scores, a significant proportion demonstrated only "Fair" (15.8%) or "Poor" (6.8%) knowledge. This uneven distribution suggests that while awareness campaigns have been moderately successful in promoting general knowledge, there are still notable gaps in symptom recognition, risk understanding and preventive practices.

Participants with limited educational backgrounds and those residing in rural areas were disproportionately represented among the "Fair" and "Poor" categories, reinforcing the need for tailored educational interventions in these communities. Simplified educational materials, including visual aids, infographics and community-based workshops, can be effective in enhancing awareness in such populations. Furthermore, integrating strabismus education into school health programs can ensure children, parents and teachers are equipped with the knowledge to recognize early signs and seek timely treatment.

Implications for Public Health and Future Interventions

The findings of this study emphasize the urgent need for comprehensive public health initiatives aimed at improving strabismus awareness. Educational campaigns should focus on dispelling misconceptions, particularly the belief that strabismus is purely cosmetic or untreatable. Community-driven interventions should utilize digital media, visual demonstrations and culturally appropriate content to engage rural populations effectively. Additionally, leveraging school-based health programs to screen for strabismus and educate teachers and parents about early signs can significantly improve early diagnosis rates [8,9].

Healthcare providers must also play a proactive role in promoting eye health awareness. Integrating strabismus screening into routine eye check-ups, particularly in pediatric clinics, can ensure earlier diagnosis and prevent the progression of visual impairment. Ophthalmologists and optometrists should offer counseling to parents about preventive strategies, such as promoting balanced diets rich in vitamin A and encouraging regular eye exercises in children diagnosed with mild strabismus [10,11].

Employers and workplaces can also contribute by promoting routine eye checkups among employees, particularly those in visually intensive occupations that may exacerbate undiagnosed strabismus. Workplace awareness initiatives can emphasize the importance of early detection and treatment to preserve both vision quality and professional productivity [11,12].